Water Bears In Space

Our own Mary Courtney, an Honorary Rotarian, spoke to the club today about a science project conceived by students of the Rochester Early College International High School (ECIHS), where she teaches. First, Mary gave us a small update on the school, which had its first graduation this year. Also this year, the school started a chapter of the National Honor Society. Normally, new members of NHS are inducted by current members, but as this was a new chapter, there were no current members. So, NHS members from Palmyra-Macedon came out to induct the new charter members. Mary was proud to have Pal-Mac NHS students do the inductions, as she was a member of NHS when she was a Pal-Mac student.

Mary then got into the meat of her program, which was to tell us about the school’s involvement in the Student Spaceflight Experiment Program (SSEP). SSEP offers students from around the country the opportunity to test microgravity on a chemical, biological, or physical system aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Students develop proposals, detailing the experiment they would like to conduct and submit them through a two-stage review process. The proposals are evaluated locally and then nationally. ECIHS’ proposal was one of only 11 selected nationally for this program.

Mary Courtney, center, with Colonel Miranda and PM Rotary President Bob Yost.

The principal investigators for this experiment were Cheyanne Jeffrey and Jo’ce Hill, along with co-investigator Cierra Cannon and collaborator Vicki-Ann Aman. They decided to conduct their experiment using microscopic organisms called Tardigrades, also known as “water bears.” Tardigrades are extremophiles, organisms that can thrive in a physically or geochemically extreme condition that would be detrimental to most life on Earth. For example, tardigrades can withstand temperatures from just above absolute zero to well above the boiling point of water, pressures about six times greater than those found in the deepest ocean trenches, ionizing radiation at doses hundreds of times higher than the lethal dose for a human, and the vacuum of outer space. They can go without food or water for more than 10 years, drying out to the point where they are 3% or less water, only to rehydrate, forage, and reproduce. This drying out process is called cryptobiosis.

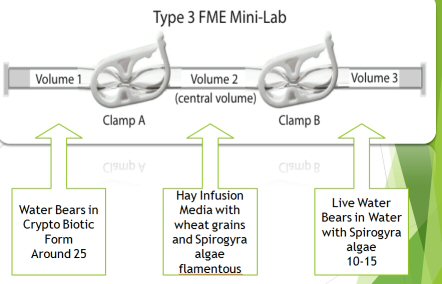

The students’ proposal focused on two experiments. The first would test to see whether rehydrated tardigrades in a microgravity environment had any structural and behavioral differences from the dehydrated tardigrades on Earth. The second experiment would be the same except with live tardigrades. The entire experiment would take place in two tubes, one-half inch in diameter, and about 8 inches long. The tubes are clamped off in two spots, creating three separate chambers. The first chamber would hold dormant tardigrades, the middle chamber would hold a wheat/water solution, and the third chamber would contain live tardigrades in a wheat/water solution.

There were two tubes – one was here on Earth at ECIHS and the other was sent to the space station. Students and astronauts were in contact and at the same time open the clamp between the first and middle sections of their tubes, allowing the dormant water bears access to the wheat/water solution and thus reviving them. At the end of the 6 week program, the tube from the space station was returned to Earth and eventually to the students in Rochester. The tardigrades in each tube were then compared. Chayanne and the other students presented their findings, along with the other 10 program researchers, at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

All the students agreed that this was an exciting, challenging, and unique experience. These students had the chance to do “real science” and that doesn’t happen to high school students every day.

Download the website sponsorship guide