The discovery hails not only the first elaphrosaur from Australia but only the second to be found anywhere in the world that lived during the Cretaceous period, shattering the previous hypothesis that these creatures thrived in the Jurassic and disappeared thereafter.

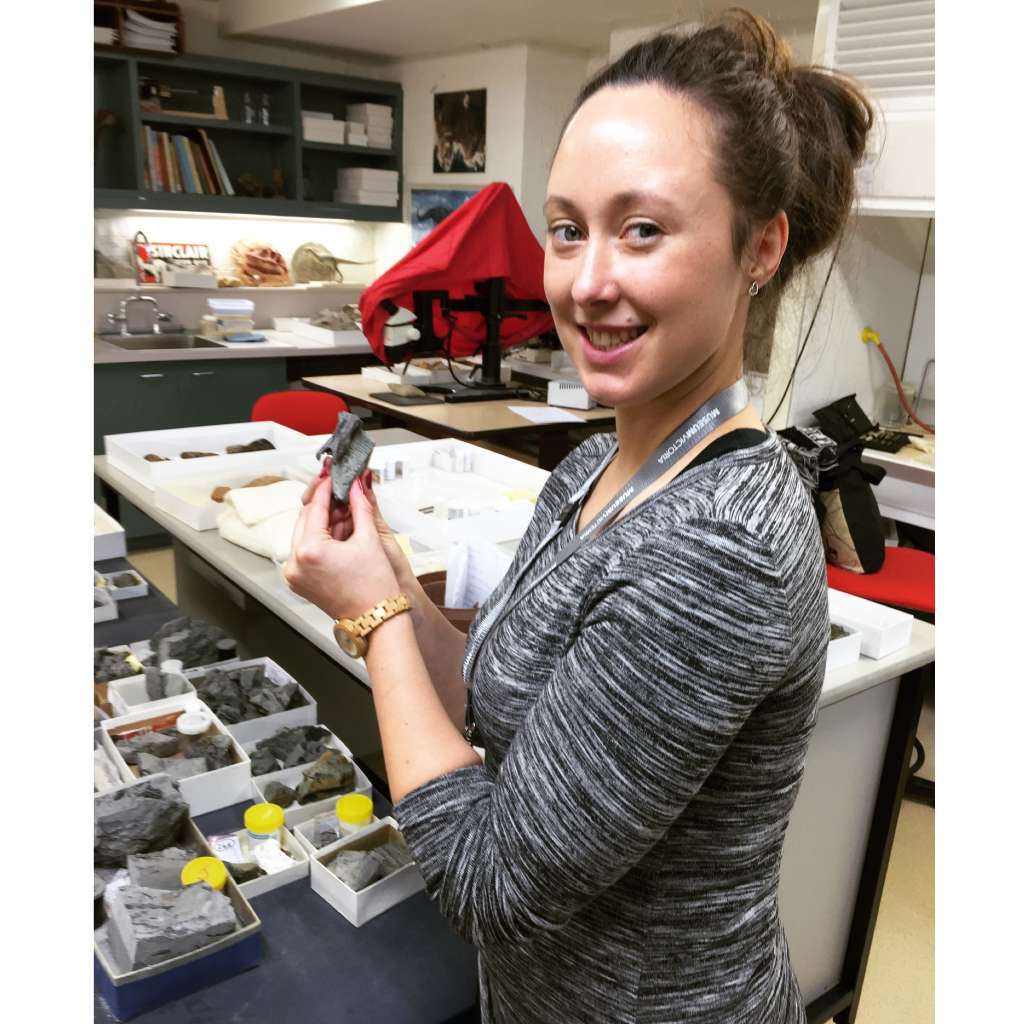

Swinburne’s Dr Stephen Poropat and Adele Pentland uncovered this new Australian dinosaur by stumbling across an incorrectly identified vertebra in the collections at Melbourne Museum around four years after it had been dug up by Dinosaur Dreaming volunteer Jessica Parker (right) near Cape Otway on Victoria’s coast.

A logical step-by-step elimination of the type of dinosaur that lay behind the vertebra and an in-depth analysis of the fossil itself led Poropat and Pentland to determine that the vertebra was in fact from a previously undiscovered type of elaphrosaur with the study1 now published in the Gondwana Research journal.

A misunderstood dinosaur

Elaphrosaurines were a type of dinosaur that ran on two legs, had a long neck, short arms and were likely to have a beaked but toothless skull as adults. They are part of a group of dinosaurs known as theropods, which had hollow bones and three-toed feet, and which were found throughout the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods.

There presently h ave been only a small number of elaphrosaur fossils unearthed across the globe, including Elaphrosaurus bambergi from Tanzania, Limusaurus inextricabilis from China, and more recently Huinculsaurus montesi from Argentina.

ave been only a small number of elaphrosaur fossils unearthed across the globe, including Elaphrosaurus bambergi from Tanzania, Limusaurus inextricabilis from China, and more recently Huinculsaurus montesi from Argentina.

Historically, elaphrosaurines had been misclassified as other types of theropods with the Tanzanian Elaphrosaurus originally believed to be an ornithomimosaur, also known as an ostrich dinosaur, Pentland told Lab Down Under.

These factors led to a dearth of knowledge about elaphrosaurs which both Poropat and Pentland had to work through to correctly identify the Melbourne Museum vertebra. Correcting similar misclassification of already uncovered dinosaur fossils could help fill these gaps, Pentland said.

“There’s every possibility that more elaphrosaurines will be found in coming years, not from the discovery of new specimens per se, but by re-examining old specimens and looking at them with fresh eyes.”

Living in a lush polar environment

The newly discovered elaphrosaur lived in the Cretaceous period when the area now known as Victoria was located within the Antarctic Circle. At the time, Australia, Antarctica and South America were all joined together as one landmass.

landmass.

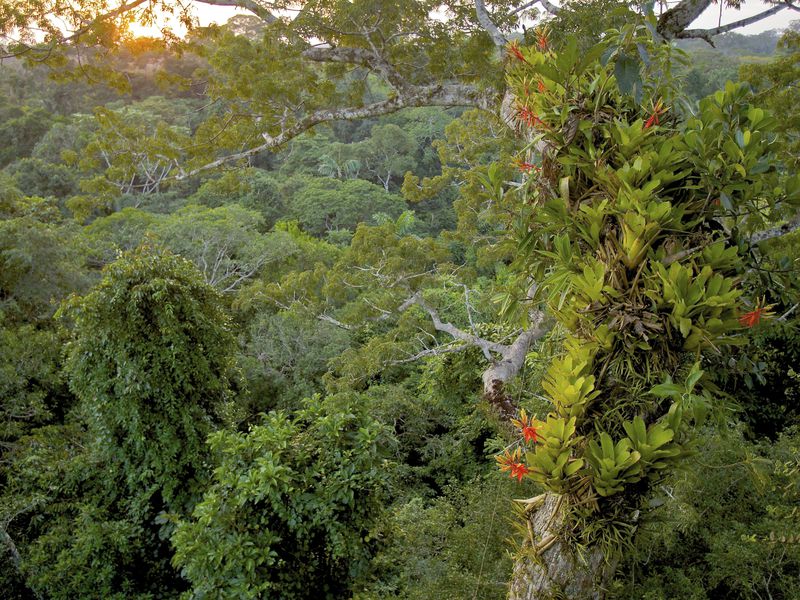

“Given that Victoria was situated near the South Pole at this time, there would have been multi-month periods of darkness and light each year. However, despite the high latitude, the flora was diverse and abundant,” Poropat said.

Because these landmasses were joined, the circumpolar currents of today, which prevent warm equatorial waters from reaching Antarctica, did not exist 110 million years ago. Back then, there was also a greater amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

As a result of these two factors, the polar regions were a lot warmer back then than they are today.

“The simple point is trees and plants were able to grow much closer to each pole than they are today because the poles were warmer,” Poropat said.

The newly discovered elaphrosaur would have lived among a wide variety of plants, including conifers, flowering plants, ferns, cycads, horsetails and ginkgos.

Full story: https://labdownunder.com/luck-and-logic-how-a-brand-new-group-of-australian-dinosaurs-was-uncovered/