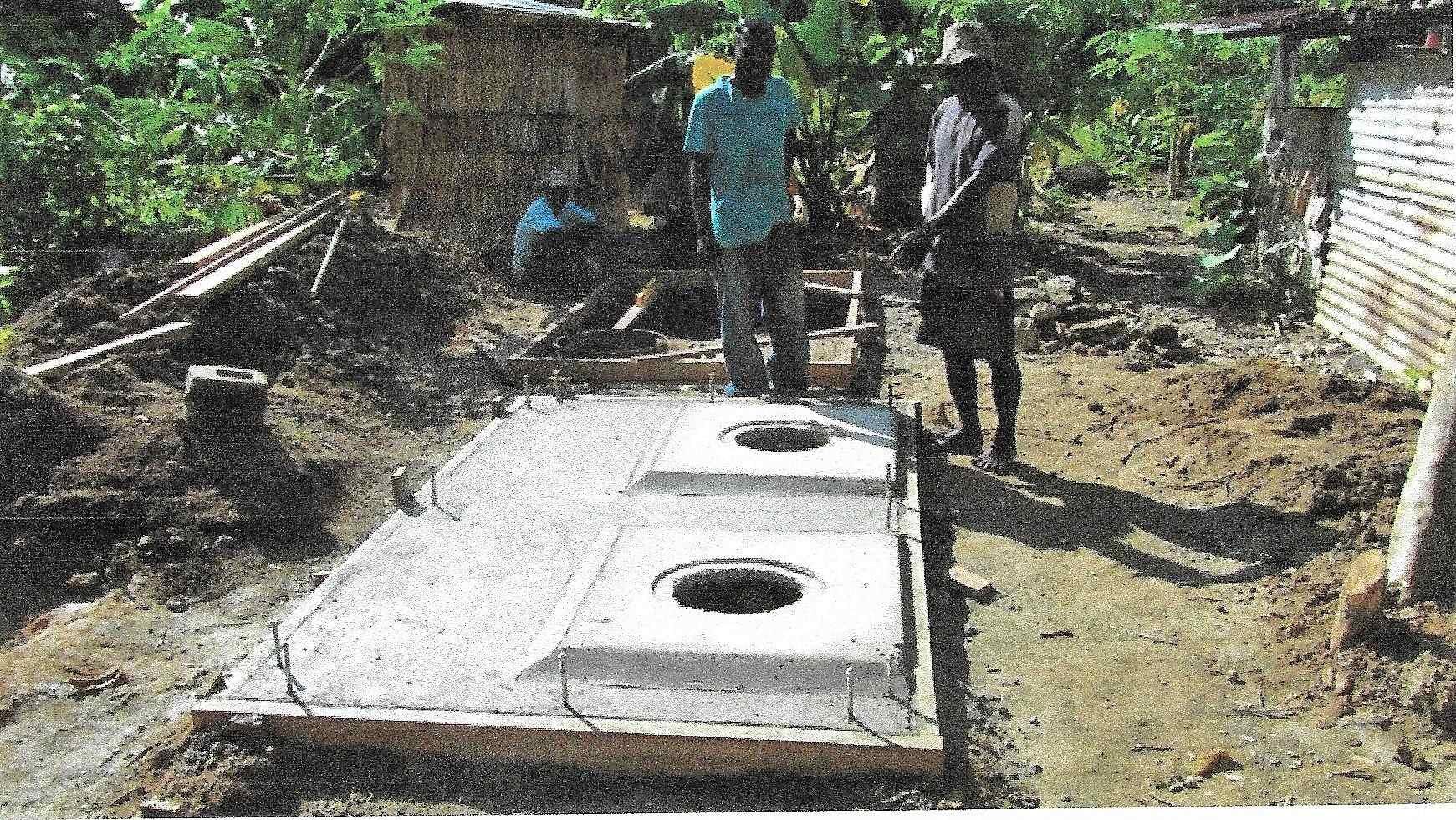

In many remote places, toilets that are connected to sewers or septic tanks are the exception, not the rule.

In many remote places, toilets that are connected to sewers or septic tanks are the exception, not the rule.

But when a group of Rotary members tried to bring these toilets to a remote island in Indonesia, the community wasn’t ready for technology that the Rotarians thought of as no-frills, but the intended recipients saw as overly complicated. “The community didn’t want it, and in fact the project had to be redesigned. It cost the project a couple of years,” says Mark Balla, president of the Rotary Club of Box Hill Central, Australia, and vice chair of the Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) Rotary Action Group. “People thought it was a great idea but didn’t think about the cultural appropriateness. That’s so important when developing a project.”

But when a group of Rotary members tried to bring these toilets to a remote island in Indonesia, the community wasn’t ready for technology that the Rotarians thought of as no-frills, but the intended recipients saw as overly complicated. “The community didn’t want it, and in fact the project had to be redesigned. It cost the project a couple of years,” says Mark Balla, president of the Rotary Club of Box Hill Central, Australia, and vice chair of the Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) Rotary Action Group. “People thought it was a great idea but didn’t think about the cultural appropriateness. That’s so important when developing a project.”

Part of the problem was that the p roject made too ambitious a leap. One tool that could help is the sanitation ladder, a graphic representation of levels of sanitation service that might exist in a community. “It helps you visualize the progressive steps to take to raise up a community from having absolutely no services to having the highest quality and most reliable services,” says Erica Gwynn, the WASH area of focus manager for The Rotary Foundation. Developed by the World Health Organization/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation, and Hygiene, the sanitation ladder concept can help Rotary clubs design a needs assessment, understand a community’s sanitation level, and set goals for a project.

roject made too ambitious a leap. One tool that could help is the sanitation ladder, a graphic representation of levels of sanitation service that might exist in a community. “It helps you visualize the progressive steps to take to raise up a community from having absolutely no services to having the highest quality and most reliable services,” says Erica Gwynn, the WASH area of focus manager for The Rotary Foundation. Developed by the World Health Organization/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation, and Hygiene, the sanitation ladder concept can help Rotary clubs design a needs assessment, understand a community’s sanitation level, and set goals for a project.

While the Foundation will not fund projects on the “unimproved” rung of the ladder, Rotary clubs that are interested in doing sanitation projects should be wary of jumping too many steps at a time. “We don’t always have to aim for the ultimate rung on the ladder, which is ‘safely managed,’” Gwynn says, although she notes that the final goal is to get there. “But sometimes it’s much more feasible and affordable to go one or two rungs up the ladder at a time. Behavior change is very difficult if you take too big of a jump.”

Balla also advises against chasing perfection. “Even in the United States, your toilet gets blocked sometimes. Perfection doesn’t exist,” he says. “It’s about continuous improvement. If you chase perfection, you’ll never start your project.”

The sanitation ladder shows the gradual steps communities may take in improving their facilities.

• This story originally appeared in the January 2021 issue of Rotary magazine.

https://www.rotary.org/en/in-communities-with-no-services-incremental-steps-can-go-long-way