The worldwide outbreak of Covid-19 has countries scrambling to source ventilators, devices that could mean life or death for the most at-risk victims.

The worldwide outbreak of Covid-19 has countries scrambling to source ventilators, devices that could mean life or death for the most at-risk victims.

How does a ventilator work?

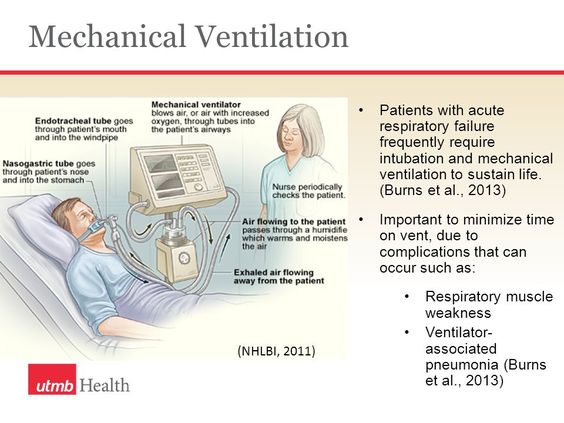

The point of a ventilator is simple: push air into lungs. Covid-19, for example, causes liquid to build in the lungs, reducing the surface area that can absorb oxygen, so the ventilator compensates with a higher dose. In contrast, if a patient is under anesthesia that interferes with the mechanics of breathing, the ventilator fills in for the patient’s muscles. In less severe cases, a mask delivers the oxygen mixture; otherwise, a tube runs deep down the patient’s airway.

In the 60-plus years positive-pressure ventilators have been in use, they’ve been tuned to the subtleties of breathing in order to treat conditions while minimizing the damage machinated breathing can cause. Early ventilators merely pushed air into the lungs at a constant rhythm; modern versions have two basic modes : one that delivers a preset volume of oxygen, one that delivers a preset pressure, plus a dual mode. Doctors are still working out which methods are best for which patients.

Ventilators also control positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), residual air pressure that prevents lungs from collapsing, a metric that varies on the patient’s condition; they can also be set to sense when a patient wants to breathe and assist with each breath rather than fully controlling breathing. Airway pressure, flow, and oxygen volume are displayed with waveforms that respiratory therapists learn to read.

Invention of the ventilator

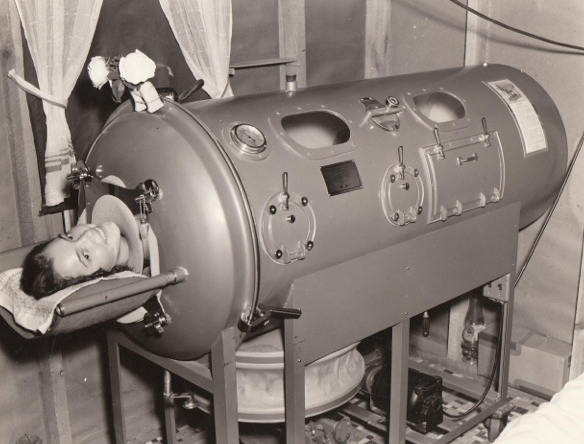

The first ventilators were mimics of nature. As humans, we breathe by expanding our chests, which creates negative pressure in the lungs, and pulls air in; when the pressure becomes positive, it’s forced out.

An “iron lung” (left) encases the body below the neck in a sealed chamber and uses bellows to vary the pressure in place of chest muscles. The first was patented in 1864. Several attempts followed, including one by Alexander Graham Bell, but the first useful breathing machine was built by Harvard professor Philip Drinker in 1929, after widespread electricity use provided a reliable source of power.

But it wasn’t very practical; Drinker himself described it as “rather cumbersome and complicated.” Biomedical engineer John Emerson managed to cut the cost in half—Drinker lost an intellectual-property lawsuit in part because so much of the underlying technology had been tried before—but didn’t change its nature: a giant canister that sealed in a human.

During World War II, Danish anesthesiologist Ernst Morch had designed a positive-pressure ventilator from “a piece of old Copenhagen sewer pipe, a piston and some castoff hardware.” After immigrating to the US, he turned it into a full-fledged device in 1954.

At the same time, Forrest Bird, a former US army pilot who had built a high-altitude breathing device during the war, was also working on a prototype ventilator, beginning with baking tins and a doorknob and applying his war experience to the body: “In that lung are rudimentary air foils. It’s like a million airplane wings all down through the lungs,” Bird said . Bird’s little green box debuted in 1955 and became the first mass-produced positive-pressure ventilator, packing the power of an iron lung into the palm of a doctor’s hand. (Bird ventilator - right)

At the same time, Forrest Bird, a former US army pilot who had built a high-altitude breathing device during the war, was also working on a prototype ventilator, beginning with baking tins and a doorknob and applying his war experience to the body: “In that lung are rudimentary air foils. It’s like a million airplane wings all down through the lungs,” Bird said . Bird’s little green box debuted in 1955 and became the first mass-produced positive-pressure ventilator, packing the power of an iron lung into the palm of a doctor’s hand. (Bird ventilator - right)

Breathing room

During the Covid-19 crisis, some designers, including experts in bioengineering and biodesign, are going back to the ventilator’s beginnings with cheap homemade prototypes, in the hopes that they will be good enough to do some good.