.jpg) If you want to read faster than most other people, there are plenty of books, classes, and videos offering to teach you how. Speed reading has been an international fascination since the 1950s, when American school teacher Evelyn Wood created a system teaching students how to read thousands of words per minute. She called it “dynamic reading,” but “speed reading” is the name that caught on.

If you want to read faster than most other people, there are plenty of books, classes, and videos offering to teach you how. Speed reading has been an international fascination since the 1950s, when American school teacher Evelyn Wood created a system teaching students how to read thousands of words per minute. She called it “dynamic reading,” but “speed reading” is the name that caught on.Speed bumps

The premise is simple: Using a few basic techniques, like eliminating distractions and reading large numbers of words at once, you can move through a text much faster, without sacrificing comprehension. That makes it possible to read hundreds of books per year, and speed through work much more efficiently.

The premise is simple: Using a few basic techniques, like eliminating distractions and reading large numbers of words at once, you can move through a text much faster, without sacrificing comprehension. That makes it possible to read hundreds of books per year, and speed through work much more efficiently.Assuming, of course, that it really is possible. For decades, scientists have argued that people aren’t capable of reading thousands of words per minute without skimming and missing details. They refer to extensive research about how our eyes and brains work together to glean meaning. But some researchers say that even if many speed-readers are frauds, it is possible to read significantly faster than the average person. It just requires the proper practice.

BY THE DIGITS

200-400: Words per minute that most college-educated adults can read and comprehend

1,200: Words per minute US president John F. Kennedy was said to read

500-600: Words per minute some experts estimate he read with good comprehension

>1 million: People who took some version of Evelyn Wood’s speed reading course, Reading Dynamics, between 1959 and 1980, including US president Jimmy Carter and actor Charlton Heston

$395: Price of the 7-session course in 1980

2,700: Words per minute that Wood claimed to read

3.5-7: Minutes it should take most college-educated people to read this email

2.5: Minutes it would take Kennedy, according to expert estimates

30: Seconds it would take Wood, assuming her claim is true

The mechanics of reading

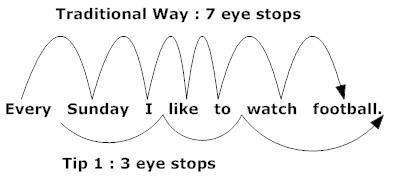

When you read, your eyes pause every few characters, before moving quickly to the next point and then pausing again. These pauses are called “fixations,” and they last just long enough to process what we see. The rapid movements in between are called “saccades.”

Reading also involves auditory processing, because even when we read silently, we pronounce each word to ourselves. That inner speech is called “subvocalization.”

Both processes are critical to comprehension. They also limit how fast you can read; according to cognitive neuroscientist Mark Seidenberg, the eyes take in seven to eight letters in each 200- to 250-millisecond fixation, adding up to 280 words a minute. Your eyes need to pause a certain amount of time to recognize and understand what you’re reading, and your inner speech can only pronounce words so fast.

Anyone can read a little bit  faster by eliminating distractions, so you don’t keep reading the same sentence over and over again. But when it comes to mental processing, there’s a trade-off between speed and accuracy. This applies to basically everything your brain does: When you try to go faster, you do a worse job at it.

faster by eliminating distractions, so you don’t keep reading the same sentence over and over again. But when it comes to mental processing, there’s a trade-off between speed and accuracy. This applies to basically everything your brain does: When you try to go faster, you do a worse job at it.

faster by eliminating distractions, so you don’t keep reading the same sentence over and over again. But when it comes to mental processing, there’s a trade-off between speed and accuracy. This applies to basically everything your brain does: When you try to go faster, you do a worse job at it.

faster by eliminating distractions, so you don’t keep reading the same sentence over and over again. But when it comes to mental processing, there’s a trade-off between speed and accuracy. This applies to basically everything your brain does: When you try to go faster, you do a worse job at it.Evelyn Wood’s “dynamic reading” courses teach you to make fewer fixations, and eliminate subvocalization entirely. This would obviously help you read a lot faster: Reading is slow because you have to recognize and pronounce all the words. If you could just recognize large chunks of text at once, and you didn’t have to worry about pronouncing anything, you could breeze through a test incredibly fast.

The question is whether that’s actually possible. For most people, subvocalization is a core part of reading. For speed-readers, it’s a bad habit we pick up as children, when we first learn to read aloud—and one they claim we can break.