ABOUT SCOTCH WHISKY Barley makes fairly lousy bread and it turns up in soup now and again, and in sundry health-food cookbooks, but it took the Scots to fully understand that if you malted it, brewed it, and distilled the result, you could convert barley into what many ardent sippers believe is the finest spirit on the planet, if you don’t ask the French. A secondary benefit was that it often led to happy times in fields of the self-same grain.

The barley was just growing there on the fells and in the glens along with heather and gorse, and the Picts, Celtic grandparents of today’s Scots, used it to make beer, which they flavoured with heather. (Whether drinking this beer had anything to do with their tendency to paint themselves blue remains a mystery.) The beer was liable to become nasty over time, as beer will in a pre-cooler world, and Irish monks, in town to explain Christianity to the blue Picts, passed along the instructions for turning barley beer into a potent spirit, a virtual water of life, that would keep forever. Keeping it, of course, eventually led to keeping it in wooden casks, the first step on the road to the malt whisky we savour today. Things rolled along fairly smoothly—invasions, famines, wars and massacres aside—for a few hundred years, with whisky being produced by crofters and traded or sold locally. Until the English arrived and brought civilisation, which by the early 18th century included taxes on whisky, which were followed immediately by tax evasion. By the end of the 18th century, there  were many more illegal stills than licensed operations north of the River Tweed. By 1820, excise officers were seizing 14,000 illegal stills per year, and it is estimated that half of the whisky poured down Caledonian throats was tax-free. A more reasonable licensing tax in 1823 gave the edge, along with modern distillation methods (thought by some to be a product of the Industrial Revolution on a par with the railroads) to licensed distillers, some of whom are still in the business of boiling barley wine today. The moonshiners persisted valiantly for some years but eventually all but disappeared. Today, distilleries will take you on hikes along old smugglers’ trails, although locals will also tell you that any trail you might come across was likely to have been a smugglers’ trail at one time. were many more illegal stills than licensed operations north of the River Tweed. By 1820, excise officers were seizing 14,000 illegal stills per year, and it is estimated that half of the whisky poured down Caledonian throats was tax-free. A more reasonable licensing tax in 1823 gave the edge, along with modern distillation methods (thought by some to be a product of the Industrial Revolution on a par with the railroads) to licensed distillers, some of whom are still in the business of boiling barley wine today. The moonshiners persisted valiantly for some years but eventually all but disappeared. Today, distilleries will take you on hikes along old smugglers’ trails, although locals will also tell you that any trail you might come across was likely to have been a smugglers’ trail at one time. The whisky these early legal distilleries (the first licensed one was George Smith’s Glenlivet, in, well, the glen of the river Livet, where he’d been producing a pretty fair whisky for some time) was made from the traditional malted barley, sprouted and then dried over peat fires. This was from necessity—the forests that covered the highlands in Scotland had been clear-cut, denuded of trees, long before the licensed production of whisky, leaving peat the practical source for drying the malt in the early distilleries. The practice of double-distilling in copper pots, the first still producing what are known as low wines, the second reducing that distillation to a more palatable spirit, was introduced very early. Not long after, the invention of the continuous column still in the 1830s (thought by some pot-still advocates to be a step backward in the Industrial Revolution) brought faster, cheaper production of a light grain whisky, made from cereal grains including unmalted barley, corn and wheat. Almost immediately whisky merchants discovered that the depth of flavour in copper pot-still malt was such that it could be diluted with large percentages of this grain whisky and still retain the taste character, although in a softer, gentler incarnation which, to their delight, also sold quite well. as low wines, the second reducing that distillation to a more palatable spirit, was introduced very early. Not long after, the invention of the continuous column still in the 1830s (thought by some pot-still advocates to be a step backward in the Industrial Revolution) brought faster, cheaper production of a light grain whisky, made from cereal grains including unmalted barley, corn and wheat. Almost immediately whisky merchants discovered that the depth of flavour in copper pot-still malt was such that it could be diluted with large percentages of this grain whisky and still retain the taste character, although in a softer, gentler incarnation which, to their delight, also sold quite well. Among the earliest blends were Dewars, Haig, and Black and White. Relatively quickly, blended whisky dominated the international Scotch trade, until 90% of the sales of malt whisky was in blends. In England, malt whisky dominated, and still dominates, to the extent that the word whisky brings you a malt whisky from Scotland unless otherwise stipulated. The resurgence of single malts—malt whisky from a single Scottish distillery, blended only with other whiskies from the same source—has eaten into the dominance of blends to some extent, although world-wide they still represent the predominance of all malt whisky sold. To further confuse you, there is a category now called “Blended Malt.” This is a whisky made from a blend of single malts from two or more distilleries, but no column-still grain whisky. This was historically called “vatted malt” and, briefly, “pure malt,” and the hope is that this is the permanent nomenclature, you should pardon the expression. Glossary

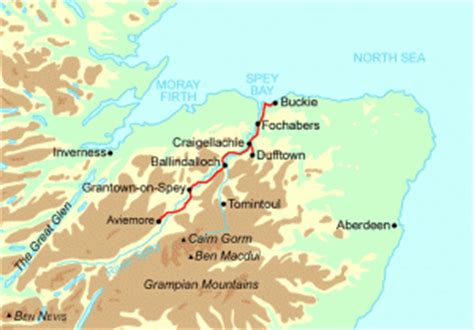

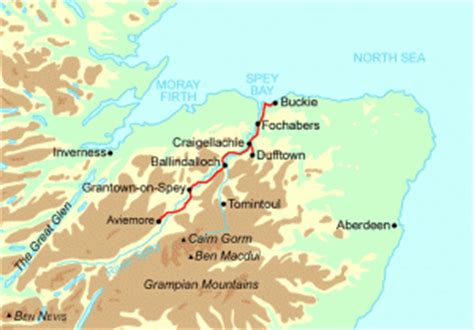

The Highlands. A large and diverse area north of Dundee in the east and Greenock in the west, minus the Spey River valley. The whiskies are generally unpeated or lightly peated, medium-bodied and will range from lush, rich and sweet to floral. Speyside. The central northern par t of the country, the valley of the River Spey, south of Inverness. The area around Dufftown, part of the Speyside Whiskey Trail, is among the oldest whisky-producing areas of Scotland, and is thought by many to produce malts with the most appeal to the American (read Bourbon-raised) palate, and represents many of the best known malts outside of Scotland, including Macallan, Glenlivet and Glenfiddich. t of the country, the valley of the River Spey, south of Inverness. The area around Dufftown, part of the Speyside Whiskey Trail, is among the oldest whisky-producing areas of Scotland, and is thought by many to produce malts with the most appeal to the American (read Bourbon-raised) palate, and represents many of the best known malts outside of Scotland, including Macallan, Glenlivet and Glenfiddich.

The Islands. All the inner and outer Hebrides, with the exception of Islay, they include Skye, reached by a bridge and home to Talisker, a heavily peated, Islay-like whisky; Orkney, reached by birds, sturdy boats and a lot of nerve and home to Highland Park, a sherry-aged whisky with a powerful sweetness; and Jura, which is rowboat distance from Islay and produces a slick, smoky, spicy whisky. The islands are less a style, although an iodine/salt/briny character is often present, than a default category. Islay, the most mispronounced place in the UK (say EYE-luh) is a big island off the west coast and home to the smokiest, most distinctively pungent and medicinal Scotches. Some sippers will also attribute a salty character to them, many being aged in warehouses within spraying distance of the sea. place in the UK (say EYE-luh) is a big island off the west coast and home to the smokiest, most distinctively pungent and medicinal Scotches. Some sippers will also attribute a salty character to them, many being aged in warehouses within spraying distance of the sea.

The Lowlands are the Scottish mainland south of the Highlands except the Kintyre Peninsula. Lowland malts, a smaller production, are sometimes called pretty—light, sweet, floral. In another time, people would sometimes call them the Lady’s Malt, but we certainly wouldn’t say a thing like that. Campbel town, the smallest area, is a port on the southwest Kintyre Peninsula with just three distilleries today, the best known of which is Springbank, which produces a rich, spicy whisky characteristic of the region’s heyday. town, the smallest area, is a port on the southwest Kintyre Peninsula with just three distilleries today, the best known of which is Springbank, which produces a rich, spicy whisky characteristic of the region’s heyday.

Finally, malt whisky is probably the most varied version of the same thing that you’ll ever taste. Always made from just water and malted barley (OK, maybe a touch of caramel for colour) yet as different as can be, a lesson in the magic of copper pots, distilling methods, wood-ageing and blending. And the fun’s in tasting them all. https://www.tastings.com/Spirits-Categories/About-Scotch-Whisky.aspx |

The Whisky D.R.A.M. fellowship (or Whisky Drinking Rotarians and Members) was started in 2015 to allow Rotarians a Whisky Appreciation Fellowship.

The Whisky D.R.A.M. fellowship (or Whisky Drinking Rotarians and Members) was started in 2015 to allow Rotarians a Whisky Appreciation Fellowship.

were many more illegal stills than licensed operations north of the River Tweed. By 1820, excise officers were seizing 14,000 illegal stills per year, and it is estimated that half of the whisky poured down Caledonian throats was tax-free. A more reasonable licensing tax in 1823 gave the edge, along with modern distillation methods (thought by some to be a product of the Industrial Revolution on a par with the railroads) to licensed distillers, some of whom are still in the business of boiling barley wine today. The moonshiners persisted valiantly for some years but eventually all but disappeared. Today, distilleries will take you on hikes along old smugglers’ trails, although locals will also tell you that any trail you might come across was likely to have been a smugglers’ trail at one time.

were many more illegal stills than licensed operations north of the River Tweed. By 1820, excise officers were seizing 14,000 illegal stills per year, and it is estimated that half of the whisky poured down Caledonian throats was tax-free. A more reasonable licensing tax in 1823 gave the edge, along with modern distillation methods (thought by some to be a product of the Industrial Revolution on a par with the railroads) to licensed distillers, some of whom are still in the business of boiling barley wine today. The moonshiners persisted valiantly for some years but eventually all but disappeared. Today, distilleries will take you on hikes along old smugglers’ trails, although locals will also tell you that any trail you might come across was likely to have been a smugglers’ trail at one time.  as low wines, the second reducing that distillation to a more palatable spirit, was introduced very early. Not long after, the invention of the continuous column still in the 1830s (thought by some pot-still advocates to be a step backward in the Industrial Revolution) brought faster, cheaper production of a light grain whisky, made from cereal grains including unmalted barley, corn and wheat. Almost immediately whisky merchants discovered that the depth of flavour in copper pot-still malt was such that it could be diluted with large percentages of this grain whisky and still retain the taste character, although in a softer, gentler incarnation which, to their delight, also sold quite well.

as low wines, the second reducing that distillation to a more palatable spirit, was introduced very early. Not long after, the invention of the continuous column still in the 1830s (thought by some pot-still advocates to be a step backward in the Industrial Revolution) brought faster, cheaper production of a light grain whisky, made from cereal grains including unmalted barley, corn and wheat. Almost immediately whisky merchants discovered that the depth of flavour in copper pot-still malt was such that it could be diluted with large percentages of this grain whisky and still retain the taste character, although in a softer, gentler incarnation which, to their delight, also sold quite well.

town, the smallest area, is a port on the southwest Kintyre Peninsula with just three distilleries today, the best known of which is Springbank, which produces a rich, spicy whisky characteristic of the region’s heyday.

town, the smallest area, is a port on the southwest Kintyre Peninsula with just three distilleries today, the best known of which is Springbank, which produces a rich, spicy whisky characteristic of the region’s heyday.