I was intrigued to read this article recently in Quartz Obsession, which sent me on a trip down “Memory Lane”:

Starting in the 1930s in Italy, d octors started offering electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients who suffered from depression and bipolar disorder. The idea was that the shock would induce a seizure, a sudden electrical storm in the brain, that could relieve some of the symptoms. The effects were longer-lasting than the drugs that existed at the time. Doctors weren’t sure why it worked, but they found that it helped a number of patients feel better.

octors started offering electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients who suffered from depression and bipolar disorder. The idea was that the shock would induce a seizure, a sudden electrical storm in the brain, that could relieve some of the symptoms. The effects were longer-lasting than the drugs that existed at the time. Doctors weren’t sure why it worked, but they found that it helped a number of patients feel better.

octors started offering electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients who suffered from depression and bipolar disorder. The idea was that the shock would induce a seizure, a sudden electrical storm in the brain, that could relieve some of the symptoms. The effects were longer-lasting than the drugs that existed at the time. Doctors weren’t sure why it worked, but they found that it helped a number of patients feel better.

octors started offering electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients who suffered from depression and bipolar disorder. The idea was that the shock would induce a seizure, a sudden electrical storm in the brain, that could relieve some of the symptoms. The effects were longer-lasting than the drugs that existed at the time. Doctors weren’t sure why it worked, but they found that it helped a number of patients feel better. By the 1950s, ECT was common practice at mental hospitals worldwide, but was quickly becoming controversial; critics said it was misused on non-consenting patients, or misapplied, such as when patients were “treated” for homosexuality. It could be risky because the voltage of the shock wasn’t standardized; memory loss was (and still is) a common side effect. Grisly depictions of ECT in films like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and novels like The Bell Jar fed rising pushback against the authority of psychiatrists, which fueled the burgeoning anti-psychiatry movement, according to The Conversation. ECT’s fall from fashion put it on the back burner for decades.

Today, it’s much safer and more widely accepted (although the issue of involuntary ECT has not disappeared). It also doesn’t cause convulsions anymore, thanks to the use of muscle relaxants. In 2012, about a million patients worldwide were estimated to receive it every year. Scientists are still not totally sure why it works, though they now know that the shock can alter a patient’s blood flow, chemical balance, and connectivity in the brain.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

My first foray into the world of psychiatry and anaesthesia was in the fifties, when I was a medical student, standing in for the resident house-doctor in a psychiatric unit. We had six patients lined up for ECT one afternoon, but the anaesthetist rostered for the job didn’t show up.

“You can give the anaesthetics, and I’ll give them the ECT”, said the registrar, my immediate superior.

“O.K.” said I, “what do I do?”

“Just give them about this much Pentothal” he said, holding thumb and forefinger apart, “and this much relaxant”, again with a demmo. After I zap them, blow in some oxygen until they start breathing again, and leave them on their side.” (Some time later, I learned the appropriate doses of thiopentone and suxamethonium, and the hazards of cholinesterase deficiency.)

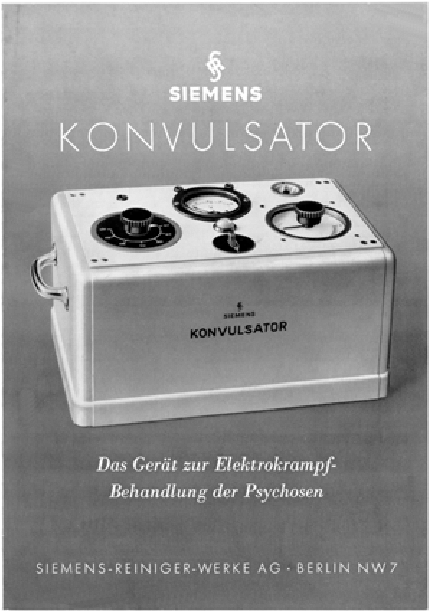

I recall the ECT machine was made in Germany, with the bright logo “Konvulsator” on the front. Our patients showed remarkable resilience, in that they all survived. Some even improved.

ECT was originally performed under anaesthesia without muscle relaxation, which occasionally resulted in fractures from the violent muscle contractions. After muscle relaxants were introduced, the convulsions were abolished.

But I was impressed by ECT as a therapy for endogenous depression, before the introduction of effective anti-depression medication. Patients who were suicidal or totally incapacitated by their illness reverted to normal lives.

The most spectacular “cure” I saw was of a catatonic schizophrenic, who was totally rigid and uncommunicatative, who became rational and mobile after treatment.

As the article says, nobody knows how it worked, but it has helped millions of patients. With over 100,000 Australian children now on antidepressants, I wonder where the world is heading.