By Diana Schoberg

Protecting the environment has always been important to Rotarians. Now Rotary has made it official

On 26 June 2020, then-Rotary President Mark Daniel Maloney made a momentous announcement: The environment would become a new area of focus for Rotary. It was one of the final achievements of a term disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and capped by Rotary’s first virtual convention. "Ultimately, the proposal passed the Trustees unanimously, the Board approved it unanimously, and I had this great satisfaction — sitting in my living room," Maloney said during a recent interview over Zoom.

The moment was built upon decades of Rotarian interest. In 1990-91, Rotary President Paulo V.C. Costa made the environment a focus of his term, creating the Preserve Planet Earth Committee to look at ways clubs and members could carry out environmental initiatives. Surveys have found that the environment is one of the top-ranking causes among members of the Rotary family.

Over the decades, Rotary members have carried out thousands of projects to protect the environment. In just five years, global grants totaling $18 million have funded projects that help support the environment while also focusing on one of Rotary’s causes, such as providing clean water and sanitation, growing local economies, and supporting education. Now that the environment is itself one of Rotary’s causes, members have even more opportunities to focus on issues that are important to them.

"The boundless creativity, enthusiasm, and determination of Rotarians everywhere, combined with their willingness to take on significant problems, make them particularly suited to make an impact on the environment," says 2017-18 RI President Ian H.S. Riseley, who chaired an environmental issues task force that championed the new area of focus.

Read on to find out how Rotary members have already been supporting the environment and to learn about new kinds of projects that will be eligible for global grant funding as of 1 July.

RECYCLING

In Campo Mourão, Brazil, only 5 percent of garbage is recycled, and workers at the local recycling facility lacked the equipment needed to increase productivity. Without a conveyor belt, they had to sort recyclable materials at tables and move them by hand, requiring extra time and effort. And their outdated press was slow and created bales of recyclables that were smaller than standard for the regional market.

Working with a local environmental program that coordinates the recycling cooperative, members of the Rotary clubs of Campo Mourão and Little Rock, Arkansas, developed a project to increase workers’ capacity to separate and process recyclable materials, providing both economic and environmental benefits. The project, supported by a $33,066 global grant in the community economic development area of focus, funded the purchase of equipment to improve worker safety and efficiency and provided environmental and financial training. Workers sorted an additional 2.63 tons of recyclables per month after the grant project was implemented, and their income increased nearly 25 percent per month.

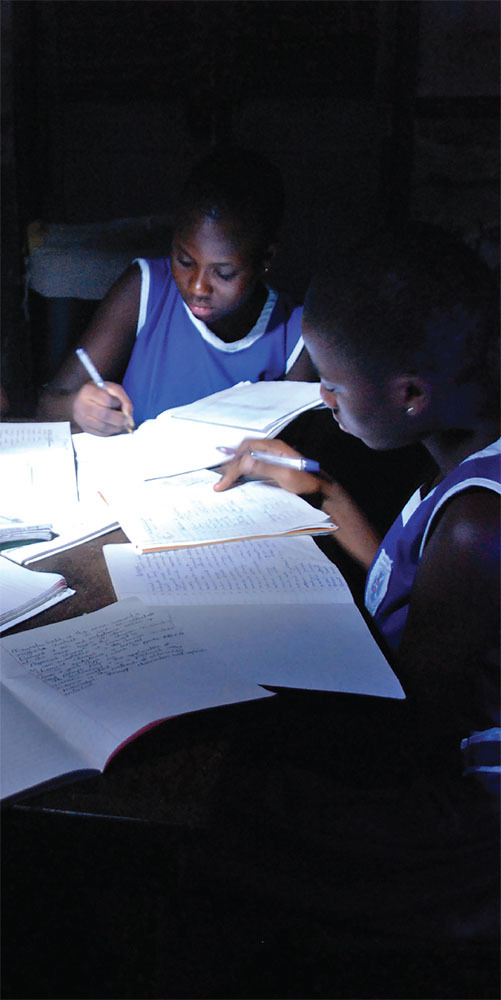

SOLAR LIGHTS

In the remote villages of Ndandini and Kyaithani in eastern Kenya, families live on less than $1 per day, and their homes are not connected to any electrical grid. Most cannot afford kerosene or paraffin to light their homes, which means students cannot see to do their homework in the evenings.

Members of the Rotary clubs of Sunshine Coast-Sechelt, British Columbia, and Machakos, Kenya, learned about the problem while working in the area on other projects. In 2014, the Rotarians embarked on a project, supported by a $101,564 global grant in the basic education and literacy area of focus, to bring environmentally friendly solar power into homes and schools.

About 1,500 students attending local schools were each provided a solar light under a rent-to-own program; students pay $1 per month, less than the cost of paraffin, for eight months, after which they own the light. The proceeds are used to provide another student with a solar light the following year. Project partner Kenya Connect, noting that the time students spend reading has tripled with the introduction of the solar lights, described the program as "a game changer in our efforts to improve the quality of education for rural schools."

The grant, combined with funding from The Rotary Foundation (Canada) and the government of Canada, also created computer labs at two schools and a solar system to provide enough power for the entire setup. More than 200 teachers received training on digital learning and ways to better make use of computers in their teaching.

WATER DIVERSION

Residents of two communities near Aurangabad, India, get their water from wells that are recharged annually by monsoon rains. But within a few months after the rains end, the wells run dry, and community members either must go further afield to fetch water or must buy it, which many cannot afford.

Members of the Rotary clubs of Aurangabad East and Chatswood Roseville, Australia, collaborated on an eco-friendly solution using a simple, traditional technology: check dams. These small dams are constructed across gullies to control the rate of stormwater flow. They decrease erosion and increase the amount of water that percolates into the ground. More than 200,000 check dams have been built across India for this purpose; a check dam constructed in India in the second century is one of the world’s oldest water diversion structures still in use.

In Aurangabad, the monsoon rains flow via a channel across a government-owned sports training center toward the sewage-contaminated Kham River. Supported by a $36,500 global grant in the water, sanitation, and hygiene area of focus, Rotary members funded the construction of two concrete check dams on the campus. The increased percolation of the monsoon rains into the ground is expected to lengthen the period each year during which the area’s 20,000 residents can obtain water from their wells. The dams have an anticipated life span of 75 years and require little maintenance.

READ MORE

WATER CONSERVATION

A series of global grant projects of the Rotary clubs of Haifa, Israel, and Coral Springs-Parkland, Florida, are using an environmental education program to unite students of different cultures and beliefs around a topic of mutual importance in the desert region: water conservation. Students from 60 schools participated in the second phase of the project, which was supported by a $152,723 global grant in the peacebuilding and conflict resolution area of focus.

Schools selected research topics of interest related to water conservation or technology, such as desalination, rainwater harvesting, or water leaks. The teachers and students were supported in their science projects through equipment and connections with experts such as engineers, biologists, or physicists.

More than 150 teachers received training in 26 training events. Most schools in Israel are separated by culture or religion, whether Jewish, Muslim, Christian, or Druze. Through the cross-cultural component of the global grant project, students visited one another’s schools to see the research projects and came together for joint field trips to visit industry facilities or to hear related speakers, giving an opportunity for interaction that they didn’t have otherwise.

SUSTAINABLE FARMING

The Indigenous Tarahumara people live on the remote slopes and canyons of Mexico’s Sierra Madre mountains, growing ancient varieties of corn and beans for sustenance. But the seeds for these plants, handed down through generations, were wiped out by a prolonged drought. In the wake of the resulting widespread hunger, many young people and women with children left their homes to beg on city streets.

Members of the Rotary clubs of Chihuahua Campestre, Mexico, and St. Augustine Sunrise, Florida, worked with a nongovernmental organization called Barefoot Seeds to facilitate community discussions with Tarahumara leaders to come up with solutions. Community leaders said they wanted seed banks and improved water storage to support continued subsistence farming.

A project supported by a $49,900 global grant in the community economic development area of focus established seed banks, demonstration farms, and plots to grow additional seeds using sustainable farming methods; reintroduced goats to improve soil fertility; installed rainwater harvesting equipment; and provided training. The project also provided solar-powered chest freezers to further extend the shelf life of stored seeds. At least 500 Tarahumara farmers received seeds, goats, or improved water access the first year.

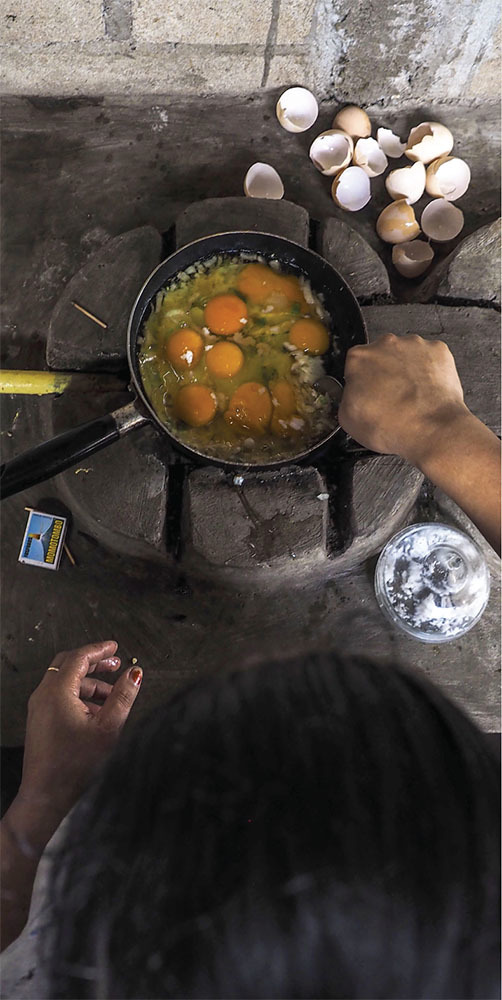

ECO-STOVES

A traditional wood fire for cooking produces the equivalent of 400 cigarettes’ worth of smoke in an hour. With around 3 billion people around the world still relying on such fires — many of them inside the home — more people die from indoor air pollution than malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS combined, according to the World Health Organization. Additionally, the black carbon emitted from these fires, which absorbs sunlight, is believed to contribute to climate change, while the need for wood drives deforestation.

Members of the Rotary clubs of Guatemala del Este and Los Angeles, California, worked together to help families living in San Lucas Tolimán, Guatemala, on the southeastern shore of Lake Atitlán. The lake, which is the primary source of drinking water for communities including San Lucas Tolimán, is severely contaminated in part because of storm runoff from areas where trees have been cut down for fuel for cooking fires. Supported by a $160,000 global grant in the disease prevention and treatment area of focus, the project provided 1,000 families with eco-stoves that vent to the outside and decrease the amount of firewood needed by 70 percent. Each stove is expected to reduce carbon emissions by 3 to 4 tons per year.

CLEAN ENERGY

The Berlin Polyclinic has been the main provider of primary health care in Gyumri, Armenia, since it opened in 1993 after a devastating earthquake in the region. But access to health care there remains limited. In conversations with medical center representatives, members of the Rotary Club of Gyumri learned that the clinic’s ability to serve patients is significantly hampered by drastically rising energy costs: In the past decade, the cost of electricity has gone up 200 percent, natural gas 70 percent, and water 50 percent. Those increases, combined with inefficient heating and water heating systems, had forced the clinic to cut its hours of operation during the region’s long winters. As a result, during the heating season — which runs from October to April — the clinic saw an average of 25 to 30 percent fewer patients.

In 2017, Gyumri Rotarians worked with the Rotary Club of North Fresno, California, on a project — supported by a $101,000 Rotary Foundation global grant in the maternal and child health area of focus — that both increases patient access and benefits the environment. The installation of photovoltaic panels, a solar hot water system, solar heat pumps, and LED lighting was projected to reduce annual energy costs by 80 percent, allowing the clinic to operate at full capacity year-round — and reducing carbon emissions by 50 percent in the process. During the first winter heating season with the new system, the number of patients served increased by 32 percent.

HOW ‘THE STARS ALIGNED’