Slow Fade - The effects of Alzheimer

Posted by Julie Bain

SLOW FADE

Alzheimer’s affects more than five million people in the United States. Now there is new hope to stop this withering disease.

Alzheimer’s affects more than five million people in the United States. Now there is new hope to stop this withering disease.Sunbeams through the bars of a crib. Rolling cookie dough with Grandmother. A flash of lightning, the smell of ozone. Waves lapping the shore. That library smell. Snow blowing sideways. Glasses of wine, peals of laughter. Onions caramelizing. Baseball games with Dad. Airplane wing over clouds. “I now pronounce you …” Ornaments on the tree. Hospital corridor. Planting flowers.

Who are you? How do you define yourself? Is it the places you’ve been, the things you’ve accomplished, the way you look? Is it your relationships, your creativity, your faith? And what if it were all taken away?

“Your sense of self requires memory,” says Rudolph E. Tanzi, a professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and co-author of the 2012 book Super Brain, with Deepak Chopra. “And when you have Alzheimer’s disease, you lose your sense of self.”

About 5.4 million people in the United States have Alzheimer’s, and that number will grow to more than 7 million by 2025. Worldwide, the projection is 100 million by 2040. The longer you live, the more likely you are to get it. And while mortality rates for Alzheimer’s are rising, funding for research is down. The disease is devastating for families and loved ones. It has the potential to bankrupt our health care system. And there’s no cure – at least, not yet.

“It’s a tsunami,” says Jeffrey L. Morby, founder and chair of the nonprofit Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (CAF, www.curealz.org) and a member of the Rotary Club of Martha’s Vineyard. “We know it’s out there, we can project it, and shame on us if we get hit with it, when we could have done something to prevent it.”

Through the efforts of CAF, and now Rotarians around the globe, there is potential for world-changing breakthroughs in Alzheimer’s prevention and treatment.

About 10 years ago, Morby was a recent retiree from Mellon Bank in Pittsburgh, after a successful career as vice chairman of that organization. “My wife, Jacqui, and I were looking for something we could do to help mankind,” he says. “We were blown away by the problems of Alzheimer’s.” Though Jacqui’s mother had developed dementia, there was more behind their motivation: They saw a need and wanted to approach it with a laser focus, “like you do in the venture capital world,” explains Jacqueline C. Morby, a senior adviser at TA Associates, a private equity firm.

They studied their market, the facts about Alzheimer’s disease, and found that research was stifled not only by limited funding but also by a lack of “big and bold thinking.” They set up a foundation with a mission to dramatically accelerate research, make courageous bets, and focus exclusively on finding a cure. And they pledged that 100 percent of funds raised by CAF would go directly to research; the founders would cover all overhead expenses.

The Morbys recruited Henry F. McCance, board chair and president of Greylock Management Corp., and Phyllis E. Rappaport, director of New Boston Fund Inc. and chair of a family charitable foundation, to join the cause. Next up: to create a research consortium. “As a venture capitalist, you’re always looking for the top people,” Jacqui says. “I heard, ‘If you want the person who knows more than anybody else in the world about brains, get in touch with Rudy Tanzi.’”

Tanzi, vice chair of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital in addition to professor of neurology at Harvard, has been a pioneer in finding genetic causes of neurological disease. He was in his early 20s in 1983 when he co-discovered the gene responsible for Huntington’s disease, which causes degeneration of nerve cells in the brain. As part of his doctoral thesis at Harvard, he decided to build a map of a chromosome. (This was before the Human Genome Project, which began around 1990.) He picked chromosome 21 “because it’s the smallest one, and I just wanted to get it done,” he laughs. He became the world’s go-to expert on chromosome 21 – which turned out to be a fortuitous choice.

When he learned that people with Down syndrome are at high risk for Alzheimer’s disease, Tanzi speculated that there might be an Alzheimer’s gene on chromosome 21. (The most common form of Down syndrome is caused by an extra copy of that chromosome.) He discovered the first gene known to be associated with early-onset Alzheimer’s in 1987, then discovered two more. “And I never went back; I have just kept going with Alzheimer’s ever since,” he says.

In the early days, Tanzi had no personal reason to focus on Alzheimer’s, but that changed. As he wrote in Super Brain, “I went into Alzheimer’s research to solve a difficult physiological puzzle, but just as important was the stirring of compassion I felt, especially after I watched my own grandmother succumb to this terrible disease.”

The Morbys met with Tanzi in 2004, as he was gearing up to find the genes responsible for the more common late-onset form of Alzheimer’s in people over 60. “While Jacqui and I may not understand everything about Tanzi’s genetic discoveries, we do know how important they are,” Morby says. Tanzi put together a dream team of world-class researchers to carry out CAF’s strategy. In no time, they were identifying new Alzheimer’s genes, and based on what they were learning from the disease-associated mutations in those genes, working on possible drug therapies.

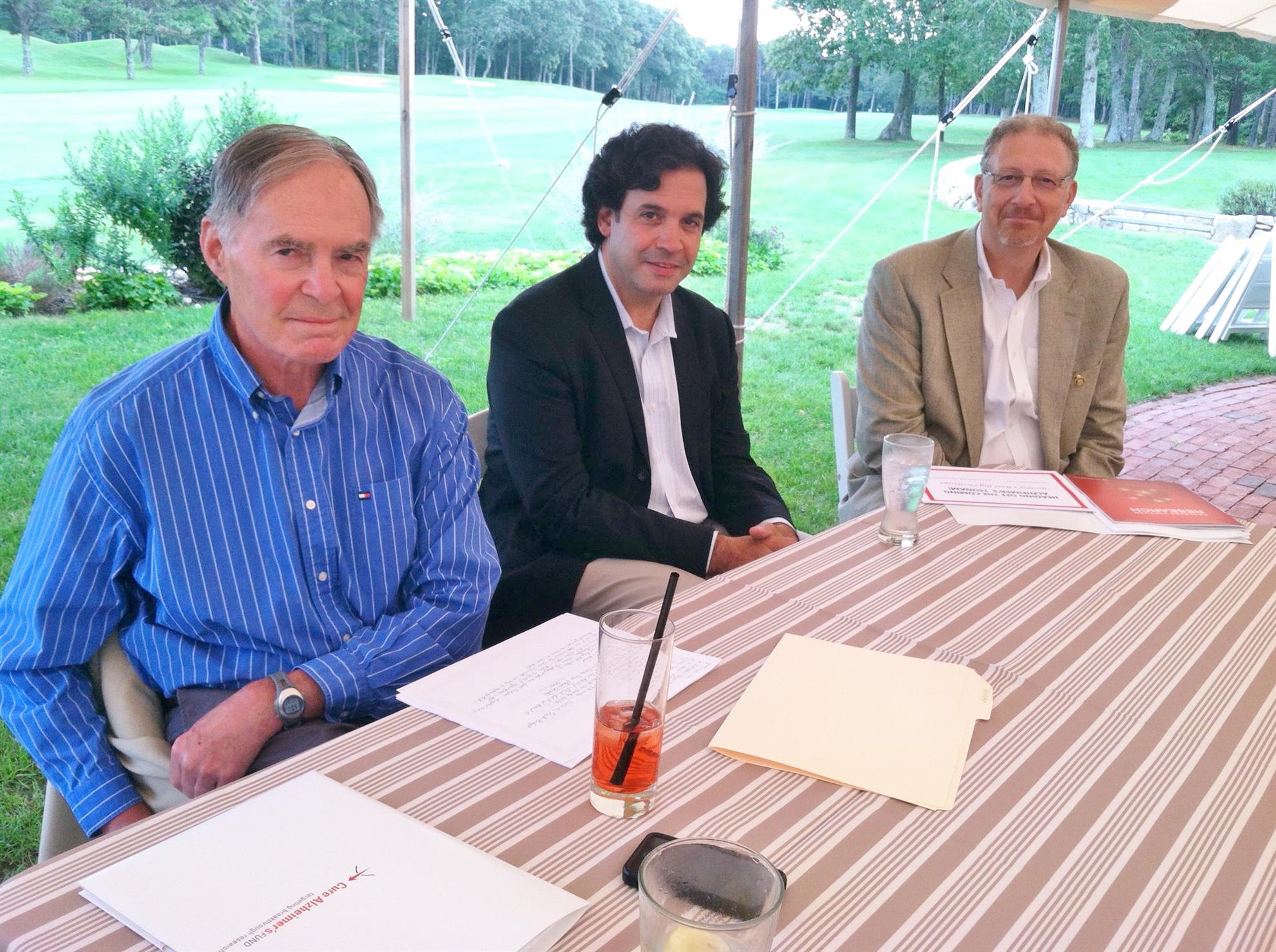

The Morbys met with Tanzi in 2004, as he was gearing up to find the genes responsible for the more common late-onset form of Alzheimer’s in people over 60. “While Jacqui and I may not understand everything about Tanzi’s genetic discoveries, we do know how important they are,” Morby says. Tanzi put together a dream team of world-class researchers to carry out CAF’s strategy. In no time, they were identifying new Alzheimer’s genes, and based on what they were learning from the disease-associated mutations in those genes, working on possible drug therapies.These accomplishments were moving CAF closer to its goal. But the founders wanted to speed up funding and research. In 2010, by a chance meeting, Rotary entered the story. Jeff and Jacqui Morby were having dinner at the Vineyard Golf Club on Martha’s Vineyard. Somehow a drink spilled, and a man sitting at the next table jumped up to help, picking up ice cubes. It was Dick Pratt, a longtime member of the Rotary Club of Martha’s Vineyard. “We started talking, just being friendly,” Morby says. “Pratt asked me what I was doing, and I told him about being chairman of the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund, and how I was dedicating my time to try to find a cure.” They talked for hours, and Pratt invited Morby to speak at a club meeting.

His talk was a hit. “Most Rotarians have somebody in their family or a friend who’s had Alzheimer’s,” Morby says. “And people are terrified that they’re going to get it.” The presentation started a chain reaction: Morby spread his message from one club to another, then to District 7950 (parts of Rhode Island and Massachusetts), and at the Rotary institute for his zone. Clubs began fundraising for a cure. The Martha’s Vineyard club enlisted comedian Tim Conway to headline an event, and that led to an invitation for Morby to hold a breakout session at the 2012 Rotary International Convention in Bangkok, Thailand. The next year, Tanzi joined him at the Lisbon convention. “We were overwhelmed with support from Rotary,” Morby says. “We had to turn people away because the room wasn’t big enough.”

Michael Curren, a member of the Rotary Club of Reading, Mass., who joined CAF as senior vice president in 2011, recalls: “People told us that Alzheimer’s was affecting their village or community and wanted advice on what to do. In Bangkok, a woman from South America said they were struggling with patient education, and another person, from Ohio, said, ‘We are too, and we’re doing something about it.’ When we went to Lisbon the next year, they both got up and said, ‘In the year since we met at your presentation, we flew to each other’s towns and gave talks on what we’re doing.’ As far as the connections Rotary makes, it doesn’t get any better than that.”

In 2013, with urging from Morby, Curren, and other Rotary members, the RI Board recognized the Alzheimer’s/Dementia Rotarian Action Group (www.adrag.org; Curren is vice chair, and Dave Clifton is chair). That year, Morby became a Rotarian.

They also have gained a more thorough understanding of its course. Alzheimer’s symptoms take 20 to 30 years to develop, Tanzi says, and there are three distinct phases: amyloid, tangles, and inflammation. The key is to figure out how to prevent, or treat, each one at different stages of life and disease. Tanzi calls this “matching the right treatment to the right patient at the right time.”

A groundbreaking study, published in the journal Nature in October, has set the stage for this three-phase approach to a cure. Using human stem cells, Tanzi and his team figured out how to grow brain cells in a special gel in the laboratory. They added the mutations from the first Alzheimer’s genes Tanzi had discovered, which cause the disease by encouraging the accumulation of a protein called beta-amyloid in the brain. Sure enough, amyloid formed in the dish, clumping into amyloid plaques, which signal the early stages of the disease. Tanzi calls amyloid the “match that lights the fire of Alzheimer’s.” The “fire” consists of twisted strands of another protein, called tangles, which choke and kill nerve cells from the inside. The landmark experiments showed for the first time that amyloid causes the tangles to form, answering the biggest question in the field in the last 30 years.

The researchers also determined that the amyloid plaques cause the activation of an enzyme called GSK needed to make tangles. That gives them hope of creating a drug that can turn off the enzyme and stop the growth of tangles, and thus the progression of the disease.

But if you could slow or stop the amyloid production in the brain in the first place, Tanzi says, you could prevent the disease. A promising medication, already in early development, could be used in a way similar to statin drugs, which lower cholesterol and prevent heart disease. “By uncovering all the genes that influence the risk for Alzheimer’s, someday we’ll be able to reliably predict people’s risk for the disease as early as their 30s,” Tanzi says. “Those at high risk could take a safe medication that could stop further progression of the disease.”

In late-stage Alzheimer’s, cell death from the tangles creates inflammation in the brain. That, in turn, kills many more nerve cells, and the disease rapidly escalates. So the third goal will be to develop medication that could fight this inflammation to slow down or even stop the disease.

While Morby says CAF has distributed over $28 million for research since it was established 10 years ago (the founders have contributed an additional $17 million, much of it going toward administration and overhead), it’s not enough for these ambitious new goals. “We have the best researchers in the world working on this, and we have a lot of information,” he says. “We’re at the point where we just need to drive this over the finish line.” He hopes more Rotarians will join the cause and help push forward the research that could lead to one of the world’s most important medical breakthroughs. “We’re in it until we find a cure,” Morby says.