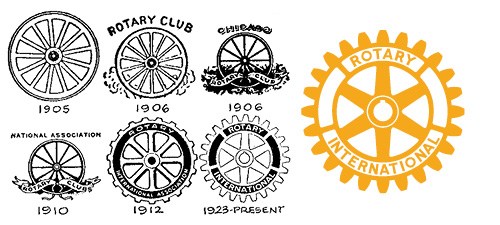

The Rotary gearwheel is one of the most familiar symbols in the world today. In some countries it is displayed at the city limits of every town with a Rotary club. But for many years, there was no standard emblem. Rotary clubs designed their own.

The Rotary Club of Chicago first used a wagon wheel, an idea attributed to Paul Harris, who reasoned that it symbolized civilization and movement. The appearance changed from time to time, depending on the engravings that the club printer had in stock. Then Montague Bear, an engraver, joined the club

The Rotary gearwheel is one of the most familiar symbols in the world today. In some countries it is displayed at the city limits of every town with a Rotary club. But for many years, there was no standard emblem. Rotary clubs designed their own.

The Rotary Club of Chicago first used a wagon wheel, an idea attributed to Paul Harris, who reasoned that it symbolized civilization and movement. The appearance changed from time to time, depending on the engravings that the club printer had in stock. Then Montague Bear, an engraver, joined the club and offered to design a permanent emblem. Members rejected his first idea – a plain buggy wheel – as looking “lifeless and meaningless.” To give the appearance of action, Monty added clouds of dust ahead and behind the wheel. He also placed the word “Rotary Club” above it. Rotarians used this design for a time until one observant member pointed out that a wheel would not generate clouds of dust in front of it! Monty removed the offending clouds and that design remained the emblem for Chicago and many other clubs, the only difference being that many other Rotary clubs added local landmark designs along with their own city name on a banner over the wheel.

At the 1912 Convention, the Board of Directors appointed an executive committee to develop a standard emblem. They worked quickly adopting some ideas of other clubs such as adding cogs to the working wheel, symbolic of the members working together-literally interlocked with one another to achieve organizational objectives. They even added a banner proclaiming “Trade Follows The Flag” and…for a patriotic touch – an eagle! Because this came from Club 19 in Philadelphia, there were 19 cogs on the wheel.

The 1912 convention approved of this design but removed the eagle and the banner. To assure uniformity, the individual clubs’ name was replaced with the organization’s name. But because on a pin, it was too big to fit the whole name of the club, they abbreviated it to “Rotary International”.

Yet despite this acceptance and subsequent publication, there were an astonishing divergence of artistic expression in the local clubs emblems. Some clubs designed wheels with eight spokes, others with 10, others with none at all. Some had 16 gear cogs, some 20, some had none.

In 1918, Charles Henry Mackintosh started a campaign to amend the design. Citing objections from Oscar Bjorge, a distinguished engineer, he wrote to the RI President: “A cogwheel with 19 cogs is an anachronism to engineers.” They lobbied for six years to correct the emblem. They argued that “it has square-cornered teeth of disproportionate size, the cogs were irregularly spaced, and it was an insult to engineering!”

From Bjorge’s hospital bed (where he was recovering from an appendectomy), he sketched out a new wheel with six spokes and 24 teeth. Finally he added a keyway which locks a wheel to a hub, thus making it a “worker” and not an “idler.” His exact specifications were adopted by the 1929 Dallas convention. Rotary’s emblem as remained unchanged ever since

From: A Century of Service – The Story of Rotary International,” by David C. Forward, 2009